The Simple Math Of Improvement

When the late Kobe Bryant was 11 years old, he played a full 25-game basketball season without scoring a single point. “I was terrible,” he said. “Awful.” He realized that he wouldn't be able to catch up to his opponents in a week, or even a year.

Kobe had to shift to a long term mindset of getting better incrementally over time:

“I had to take a long-term view...And I said, ‘Ok, this year, I’m going to get better at dribbling. Next year, shooting. The year after that, creating my own shot.’ So forth and so on.’ When I came back after the summer, I was better.”

What set Kobe apart from others his age was his focus on incrementally improving his fundamentals. Whereas his competition relied on their athleticism and natural ability.

“Because I stuck to the fundamentals, it caught up to them.” By age 14 he was a dominant basketball player. His process of building up to that level of expertise piece by piece stuck with him:

“It was piece by piece. It was the consistency of the work. Monday, get better. Tuesday, get better. Wednesday, get better. Do that over a period of time—three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten years—you get to where you want to go.” “It’s simple,” he said. “It’s simple math.”

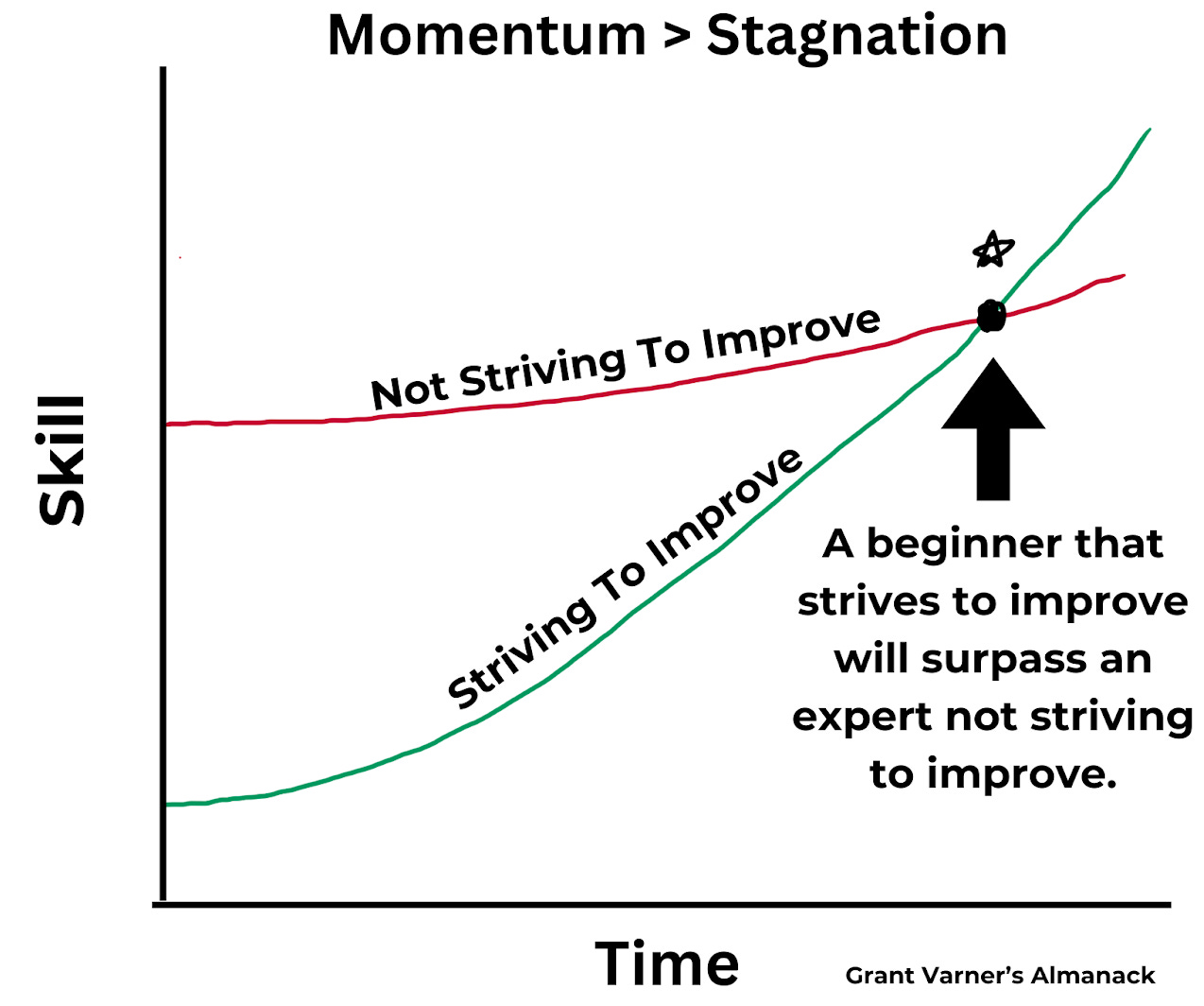

A Beginner Will Surpass The Expert When They Improve

In physics, relative motion says that an object with more momentum will eventually pass another object with less momentum. In continuous improvement, a beginner striving to improve will always surpass an expert not striving to improve—if you have a long term view.

This means two things:

If you’re a beginner committed to improving, you will eventually pass the less committed experts in your field.

If you’re an expert, you need to keep improving, or you’ll get passed by a beginners that are committed to improvement.

The Adaptability Of The Human Mind And Body

Your brain has an incredible ability to adapt to the stimulus it receives. When you push beyond your comfort zone mentally, your brain rewires neural connections in a phenomenon called neuroplasticity. This changing of the brain expands your ability to become better at what you were practicing.

In 2000, The Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest record was 25 hot dogs eaten. In 2021, Joey Chestnut shattered that record, eating 76 hot dogs.

Outside of some genetic advantages—like being a basketball player over 7 feet tall—you can accomplish virtually anything with continuous improvement and time.

To quote Carol Dweck, author of Mindset: “Genetic ceilings determine your limit, but effort determines how close one gets.” Adaptation through deliberate practice is a uniquely human quality, and it’s within anyone’s grasp—even if you don’t have 10,000 hours.

The 20 Hour Rule

During a 2013 Ted Talk, Josh Kaufman—a new father—gave a realistic path to expertise for others like him who don’t have 10,000 hours to practice.

Kaufman deconstructed the science of continuous improvement to find that it takes just 20 hours—in 20 minutes bursts of deliberate practice—to become really good at something. That’s just two months of waking up a little early every day to improve.

To prove it, Kaufman learned to play the ukulele in the weeks leading up to his Ted Talk (the song starts at 15:50).

His performance was awesome, hilarious, and left the crowd roaring with applause. Following the performance, he shared a secret, and the punchline of the talk:

“By playing that song for you, I just hit my 20th hour of practicing the ukulele.”

You can be great at anything. You just need to practice the right way. Using deliberate practice.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice is the how of continuous improvement. It’s how Kobe got better at basketball. It’s how Kaufman learned to play the ukulele. And it’s how you’ll become great at whatever you want to get better at.

Have specific defined goals.

Receive immediate feedback.

Constantly push beyond your comfort zone.

Cyclically depend on, and produce new mental representations.

Kaufman simplified this process with the ukulele by learning just enough to self-correct. Reaching this minimum level of expertise enabled him to give feedback to himself after making a mistake. Then he took 20 minutes a day to push beyond his comfort zone.

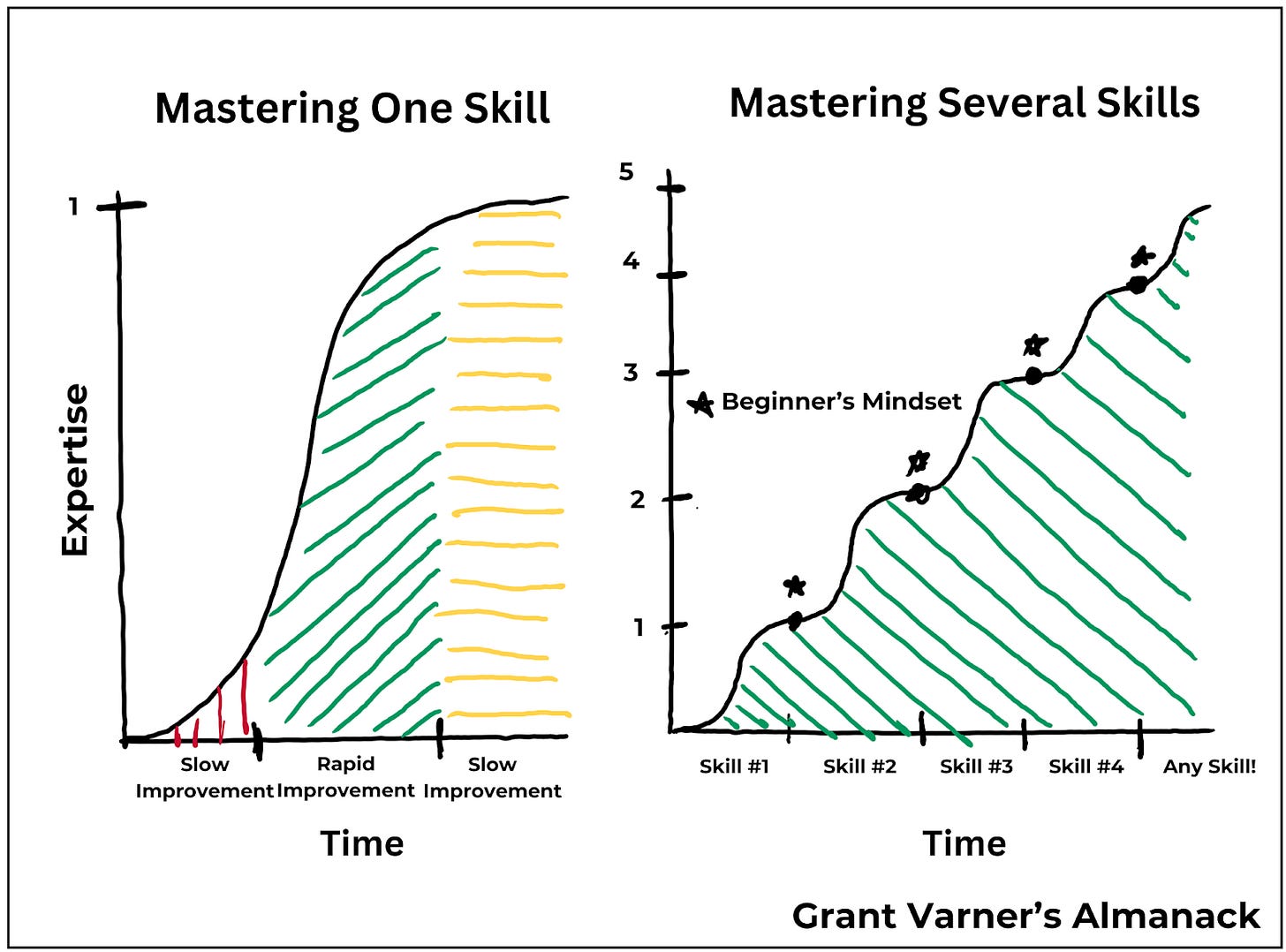

Kobe used a similar approach, picking a new skill to focus on each year. Whereas Josh Kaufman practiced for 20 hours to get really good at ukulele, Kobe put in well over 10,000 hours, and became the best in the world.

Becoming really good at something vs. becoming the best at something are two very different goals. Tactically, they’re achieved the same ways. But becoming the best requires a long term commitment to improving.

“A journey of a thousand miles starts with one step.” — Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

Your Capacity For Improvement Has No Limit

A decade from now, wouldn’t it be great to have improved in the areas most important to you? This reality is within your grasp. And it doesn’t require undue stress or burnout either. It’s a matter of working smarter, not harder.

Three things are true:

The threshold for expertise is higher today than it’s ever been.

Your capacity to become an expert is higher today than it’s ever been.

Your capacity for adaptation has virtually no limit.

— Grant Varner